In the 1820s and 1830s, desperate agricultural labourers in England began to revolt. There were a few factors involved in causing this unrest but Land Enclosure is considered to have played a large part.

Before Enclosure

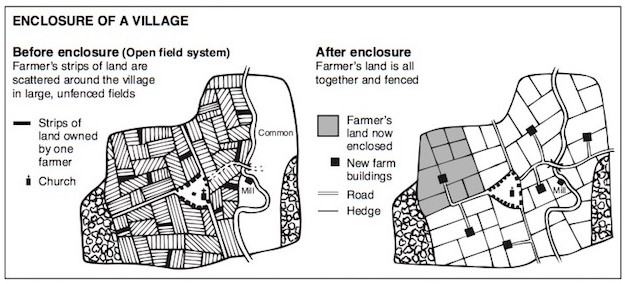

Before enclosure, villages used an open field system of farming. Large open fields were divided into strips that would be farmed by its owners. They were often scattered, and there were no fences or hedges to divide them.

There was also an area of common land used for grazing. This was not open to the general public but was land (controlled by the lord of the manor) that people from that village had rights to use. The land would be used to pasture cattle or keep livestock such as geese, and collect turf, firewood, fruit or berries. There would be a communal consensus for when and how the land would be farmed.

After Enclosure

After enclosure, the separate strips were consolidated so that owners had unified pieces of land. These were marked out through fences or hedges with absolute property rights. No communal consensus was needed – owners could do with their land as they wished.

Enclosure of land was not new, but in the late 18th century it was now being formalised with parliamentary acts. A landowner wanting to enclose land in their parish would obtain a private Act of Parliament. Commissioners would then visit the parish to survey the area and hear claims of other land holders or those with rights to the common. The commissioners would then enclose the open fields, allocating a plot of land that was equal in size to the total strips of land a landowner previously held. The common would also be divided and given to landowners depending on their total landholdings in the parish and access they had to the common.

People who previously had common rights lost the ability to use that land to make ends meet and those who still had some rights, such as tenant farmers, were increasingly asked for rent in cash rather than stock or produce.

How were agricultural labourers affected?

Consolidating the land meant that less workers were needed. It became more common for labourers to be paid by the day or week, or employed for short periods such as harvesting, hedging, ditching and threshing. Farmhands became casual labourers with no guarantee of work, and rates of pay dropped because there were so many available workers. The problem grew worse in 1815 when the Napoleonic Wars ended, and many thousands of soldiers returned to the rural labour market.

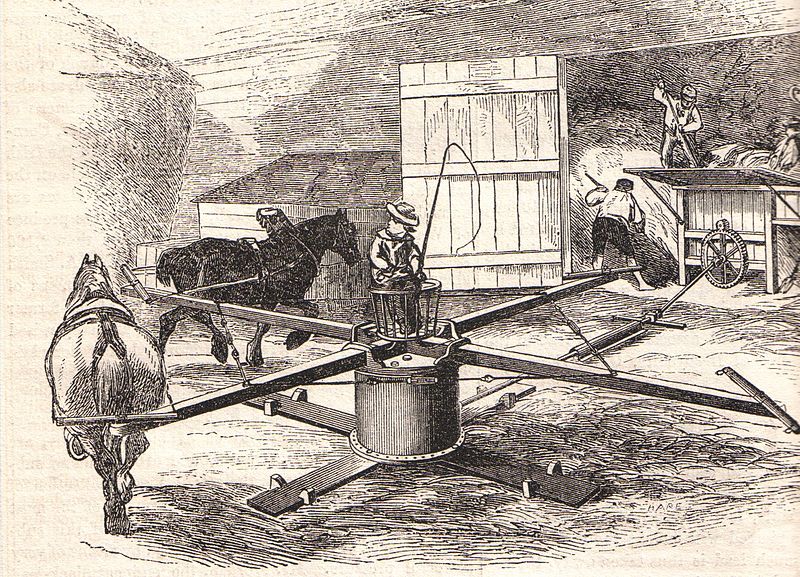

The introduction of threshing machines aggravated the situation. Farm labourers who had previously been employed to manually thresh grain over the winter months, were replaced by cheaper and more efficient horse-powered machines. Groups of agricultural labourers began to rise up, setting fire to farms and destroying machinery.

If captured, the rioters faced imprisonment, transportation, and even execution, so it was not an act to be taken lightly.

If you have ancestors who were agricultural labourers in the 1820s and 1830s, they may well have been involved in the protests.

Sources:

Norfolk County Council: Enclosure

In Our Time: The Enclosures of the 18th Century

Wheatley Village Archive: Agricultural riots of 1820s and 1830s