At around noon on Friday 31st January 1941, a lone German bomber was seen flying towards the town of Stowmarket in the heart of Suffolk. Enemy aircraft tended to fly low in the area to avoid the guns at nearby Wattisham Airfield, and this plane was flying so low under the clouds, that its swastikas could be seen from the ground.

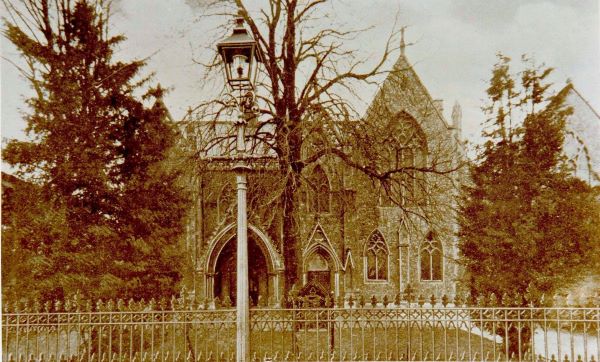

The plane flew over Stowmarket from the direction of Combs Ford, firing its guns, before circling around to fly over again, and drop a stick of bombs in the general vicinity of the market place in town. Thankfully, the busy market place was missed, but a direct hit was made on Stowmarket Congregational Church, destroying the building. Houses behind the church grounds were also struck, killing one of the residents.

I learnt about this event through “The Bombing of Stowmarket Congregational Church” by Steve Williams (2004). The book is a compilation of many reports and eyewitness accounts of that day and I found it so fascinating that I devoured the contents in one sitting! The recollections are presented in such a way that you start to feel like you know the inhabitants and their various connections to each other.

Mrs Rhoda Farrow (nee Hearn), lived at ‘Marron’ (9 Kensington Road), behind the Congregational Church. In the 1939 register, Mrs Farrow was recorded at the address with her son Ronald, daughter Marjorie and new son-in-law, Roland Wilden. Marjorie had actually married at the Congregational Church, only a month prior to the register being taken. (Her father, Rhoda’s husband Charles Farrow, had died only a few months before.)

After the bombs fell on 31 January 1941, Bernard Moye, then 16 years old, accompanied the town’s surveyor, Mr. John Black, into town to assess the damage…

When they learnt that another bomb had fallen on Kensington Road they went to the scene and found other members of the rescue party who had already managed to get two ladies out, one of whom was Mrs. Capp, who had the flower shop in the Market Place next to Woolworth’s. They had saved themselves by sheltering under the stairs of Mrs. Capp’s house, which was named ‘Floral-Dene’.

Bernard remembers seeing the roof seeming to be suspended in mid-air with nothing much supporting it. They were then told that there was no-one in next door at ‘Marron’ and that Mrs. Farrow was at the railway station seeing her son off from Forces’ leave. This tragically was not the case as Bernard remembers being in the party which, after clearing some rubble from the passageway of Mrs. Farrow’s house, they then lifted the door that lay amongst the debris and found her body laying there. Bernard commented ‘she unfortunately appeared to have arrived home at the wrong moment.'”

(excerpt from The Bombing of Stowmarket Congregational Church (2004), pp15-16)

Mrs Beatrice Smith, who lived at number 7, had been at the first aid centre on 24-hour call with the Red Cross. She would serve in the Red Cross for 51 years. In 1975, on the occasion of her retirement, The Bury Free Press (7 Nov 1975, p2) remarked that her devotion to duty had probably saved her life. The book holds quite a few of recounts of near-misses and it appears extremely fortunate that Mrs Farrow was the only person killed in the attack.

A new ultra-modern building was finally completed on the same site in 1955 and still exists (now known as the United Reformed Church). The new church’s contemporary look was very different from the previous church’s Victorian Gothic style and received mixed reactions. I can’t help but think that Stowmarket town centre would have a very different feel if the old building was still around today.

I also can’t help but think that it’s somewhat of an eerie coincidence that I was given this book and learnt of the bombing for the very first time, only a few days before the 83rd anniversary of the church’s destruction, and the death of Rhoda Farrow.

One of my favourite things about genealogy is feeling like a detective, and today gave me another opportunity to don my deerstalker and grab my pipe.

One of my favourite things about genealogy is feeling like a detective, and today gave me another opportunity to don my deerstalker and grab my pipe.