Came across something very curious last night…

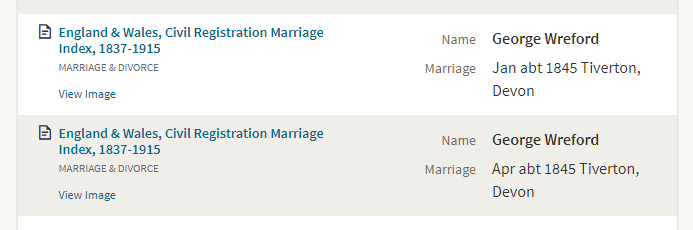

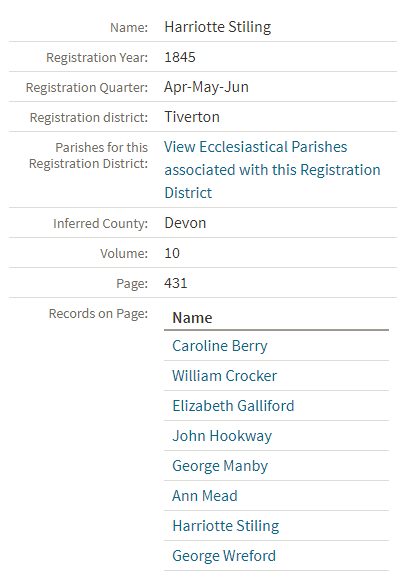

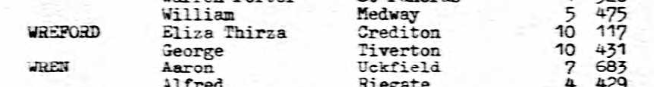

The marriage of George WREFORD and Harriet STILING (for which I have both the original parish entry AND official copy of entry, as well as the record of banns) was recorded twice in the registers – same parish, church, year and even volume – within pages of each other.

At first I thought it may be a different George Wreford since Wrefords abound in Devonshire, but Harriet is mentioned in both entries (albeit with different spelling).

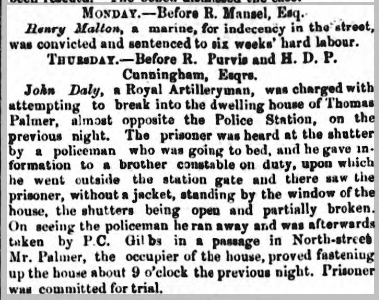

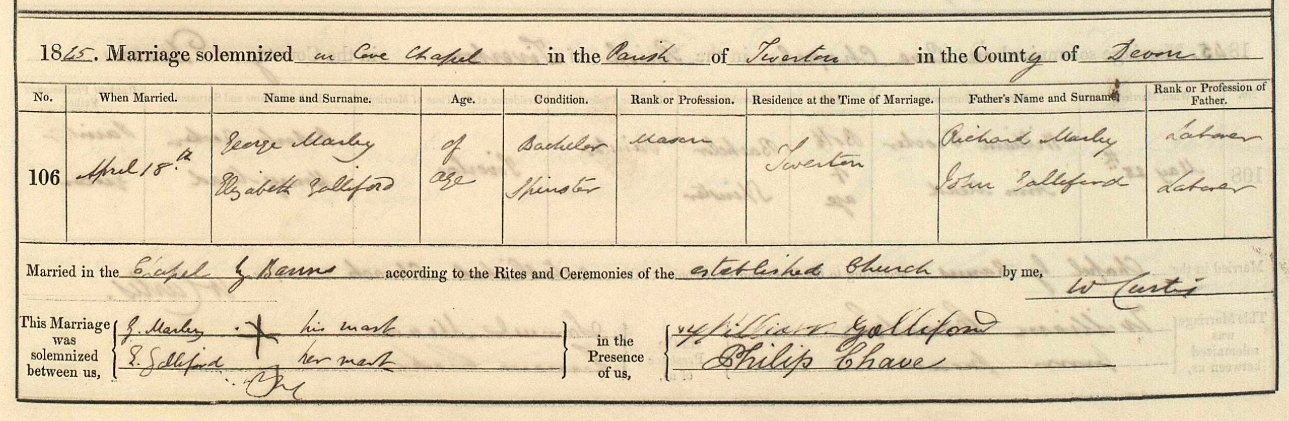

Perhaps the clue lies with the only other name from both entries – Elizabeth Galliford recorded as marrying George Marley/George Manby. Perhaps it was just recorded twice to clear up the spelling mistakes but that also doesn’t make sense as the parish records show both marriages actually took place in the April Quarter.

I have tried searching for a second ceremony in the Tiverton area via the Devon Parish Registers on findmypast but there doesn’t appear to be any.

Why would the marriage which took place in May be initially recorded in the previous quarter? I guess the next step is to order the record from page 407 although I don’t want to spend more money just to get the exact same copy sent to me.

Notes:

- I will now begin spelling Miss Stiling’s name as Harriotte as that is how she signed the register herself.

- I found out while researching this that Phillip Chave, who appears in both entries as witness and several times in the Cove registers was actually the assistant to Mr William North Row of Cove House – magistrate for Devon. I presume this meant he often ‘sat in’ as witness for these smaller ceremonies where required. I had originally thought he may have been a friend or relative.

Next Steps:

- Order Jan qtr marriage certificate

- Revisit Harriet STILING to find connection to Cove area