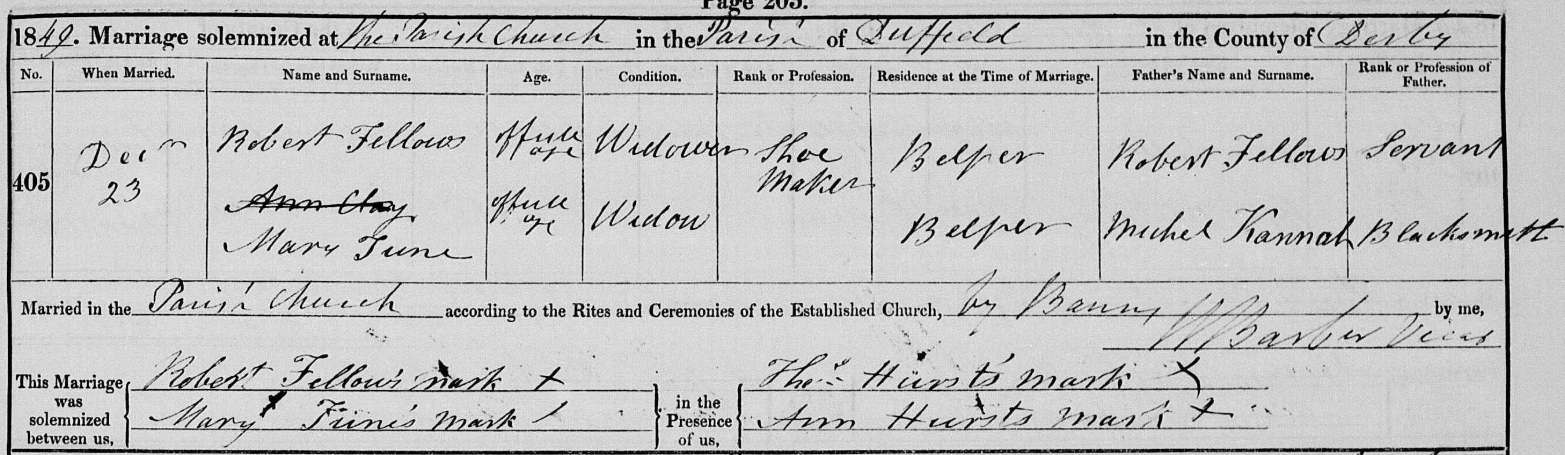

Samuel Perkins and Elizabeth Collins were both born in Market Harborough and married there in 1846. By 1851, the couple had taken up residence in Sun Yard.

The yards of Market Harborough ran off the High Street and adjoining roads, behind the more substantial shops, inns and houses. The residential yards were similar to court housing – low quality, high density property where poor people were housed, often in less than desirable conditions. Sun Yard, now demolished, was situated behind the church in which they married – roughly where Roman Way now leads off from Church Square and Adam and Eve Street.

Samuel and Elizabeth, who did not have any children, continued to live in Sun Yard until a tragic event occurred in early 1892.

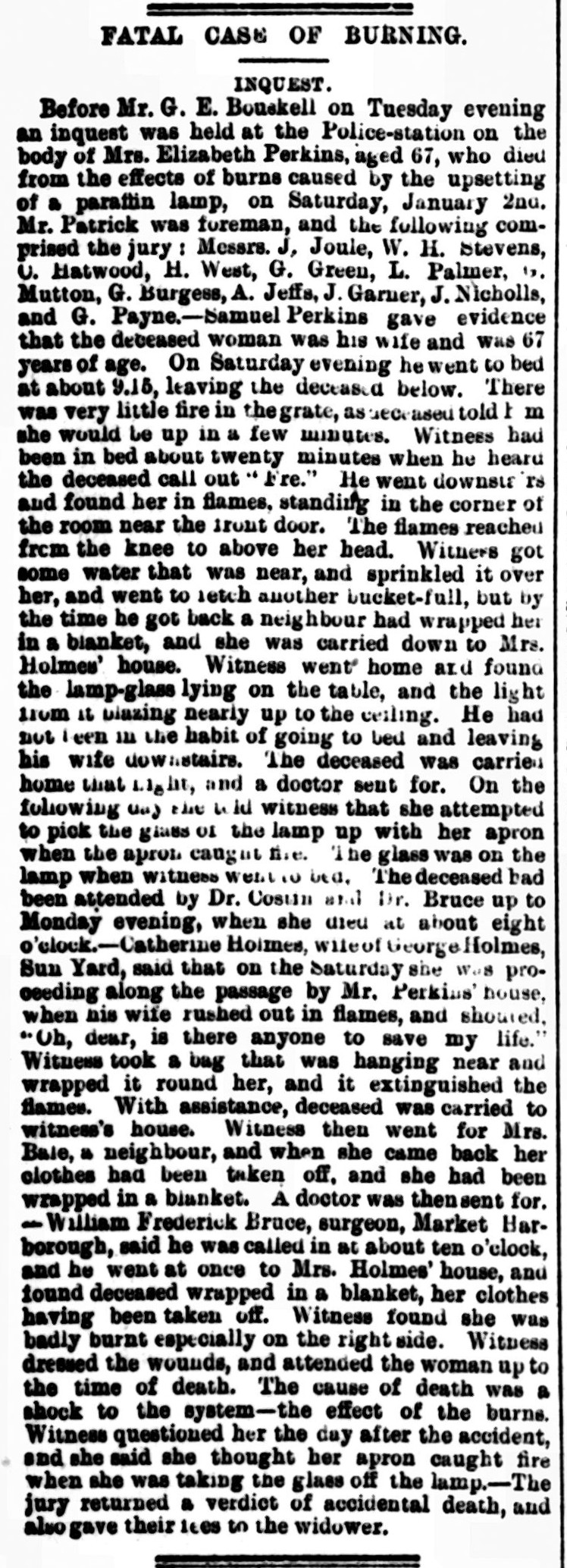

On the night of Saturday 2 January, about quarter past 9, Samuel decided to go to bed, and left his wife Elizabeth sitting by a small fire – she said she would go to bed herself in a few minutes.

After about 20 minutes, Samuel heard Elizabeth shouting, “Fire!” and rushed downstairs to find his wife in flames. She was standing in a corner near the door which led into the yard, with her clothing in flames from her knees up over her head. He threw some water over her that he kept in the room in case of fire, and went out to fetch more water.

While he was gone, their neighbour, Catherine Holmes, who had been coming down the passage at the end of the Perkins’ house, saw Elizabeth rush out in flames shouting, “Oh, dear, is there anyone to save my life?”

Mrs. Holmes took a bag (or sack) that was hanging nearby and put it around her shoulders to extinguish the flames. With assistance, Elizabeth was carried into Mrs. Holmes’ house. She went to get another neighbour, Mrs. Bale, and when she came back Elizabeth’s clothes had been taken off, and she was wrapped in a blanket.

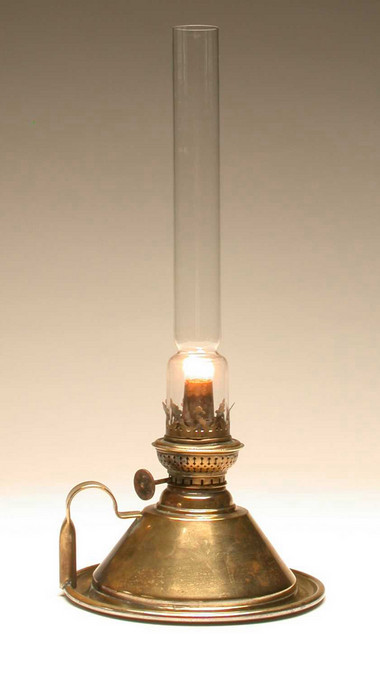

When Samuel returned to his house, he found the lamp-glass lying on the table, and the light from it blazing nearly up to the ceiling. Elizabeth was carried back home, and Mrs Holmes’ then sent one of her young sons to fetch a doctor.

The next day, Samuel asked Elizabeth how the accident happened. She said she was trying to put the glass over the lamp with her apron, when the apron caught fire.

Despite continuing medical treatment from doctors, Elizabeth died about 8 o’clock Monday evening.

An inquest was held at the police station on Tuesday 12 January.

Mr. William Frederick Bruce, the surgeon who attended her, stated that he found Elizabeth suffering from extensive burns on the body, especially on the right side, the throat, and mouth. He dressed the wounds and attended her until her death which he thought was caused by shock to the system.

Samuel said he had not been in the habit of going to bed and leaving his wife downstairs, and that when he had gone upstairs the glass was on the lamp.

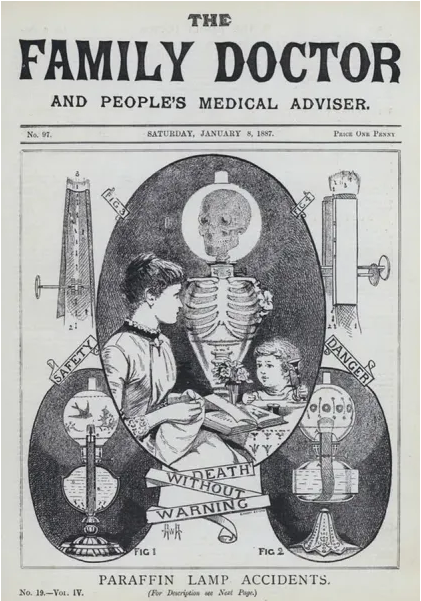

The jury returned a verdict that Elizabeth was accidentally burnt to death by the upsetting of a paraffin lamp. Touchingly, the jury, in an act of sympathy and/or charity, gave their fees to Samuel.

Poor Elizabeth was just one of many deaths attributed to the use of paraffin lamps in the home. Although there are no specific numbers and statistics, a look through the newspapers shows just how prevalent paraffin lamp accidents were in Victorian times. In an age where gas and electricity were not yet widely available (gas lighting was only introduced to Leicestershire in 1879, and electricity in 1899), these lamps offered more affordable, brighter and longer-lasting light than candles.

Elizabeth was my husband’s 3rd great-grandaunt.

She was the sister of Sarah Collins who was the wife of Thomas Ebben. Thomas died in Market Harborough in 1878, and it seems quite likely that he also died in Sun Yard, maybe even in the home of Elizabeth and Samuel.

Newspaper Sources:

- Shocking Case of Burning: Market Harborough Advertiser, 12 Jan 1892, p4, c1

- Shocking Paraffin Lamp Accident; Leicester Chronicle, 16 Jan 1892, p7, c8

- Fatal Case of Burning: Market Harborough Advertiser, 19 Jan 1892, p5, c1